Summary

- To begin with: The US is dominated by majoritarian electoral systems that constantly reproduce a duopoly of two parties. The parties have papered over this external democratic deficit by introducing internal democratic reforms, chiefly, primary elections.

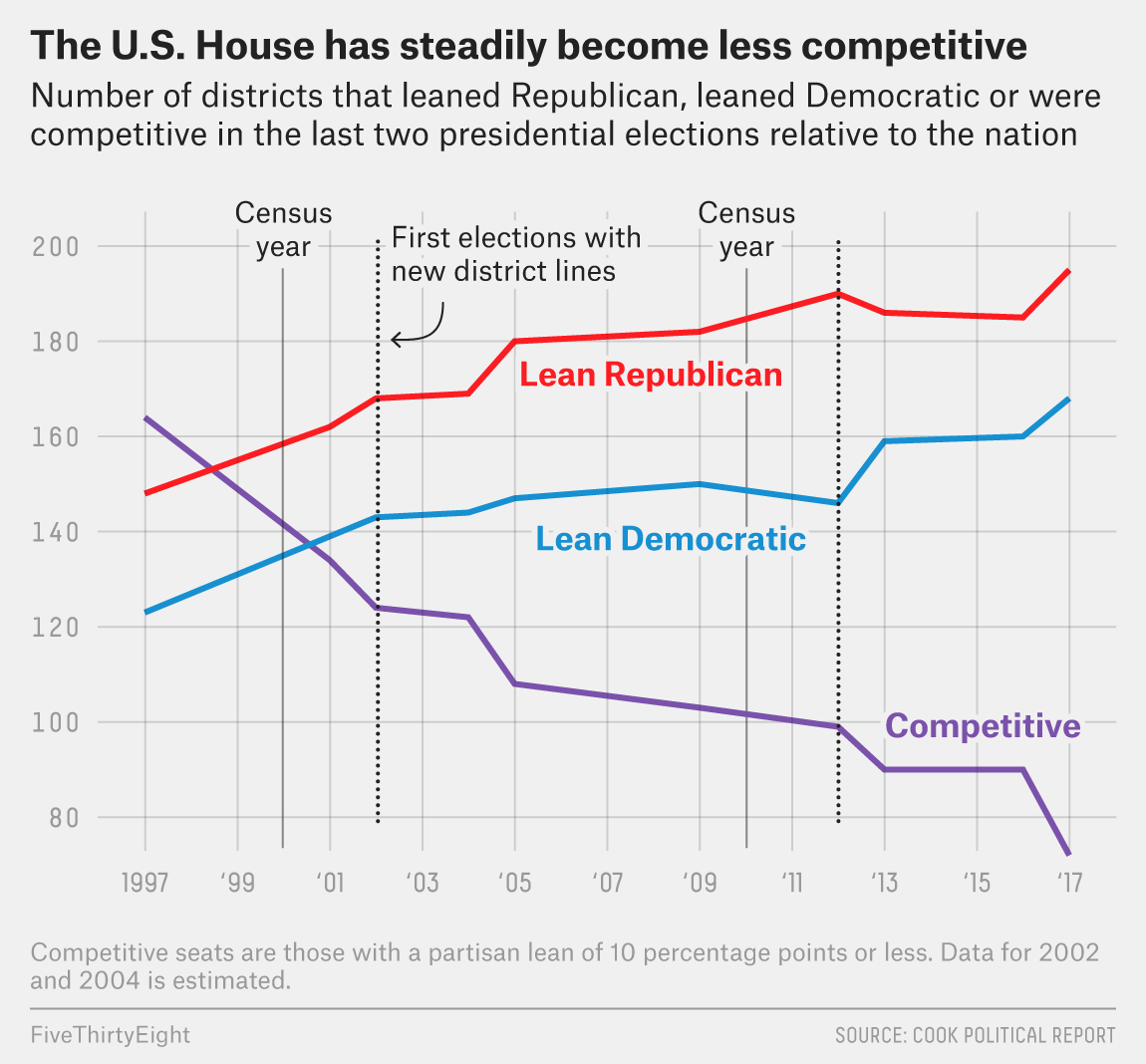

- Over the past 30 years, a ‘sorting’ of the electorate has resulted in many districts that are heavily tilted towards either the Democrats or the Republicans, with many uncontested, effectively one-party constituencies.

- This shift further increases the importance of primaries, which are dominated by the most militant party members and wealthy donors. This affects the Republican Party more because its activists and donors are more homogeneous.

- At the same time, big money from wealthy donors and business interests distorts the positions of both parties. The Republican elites advocate positions that their base does not support, such as tax cuts for the wealthy.

- This constellation is highly susceptible to a populist revolt against the party elites in the primaries - and that is exactly what Donald Trump was.

For well over a decade, US politics, and the Republicans in particular, have been sinking deeper and deeper into the swamp of unreason. But why? A recipe for the disaster.

Start with a large size and add unjust voting systems

Comparison to Europe

In Switzerland, people are quick to draw an analogy between the US capital Washington and the Swiss capital Bern. Size-wise and psychologically, a better analogy would be the EU: Washington is like Brussels, the US like the EU, and US states are like member states of the EU. Seen in this light, some of the shrill rhetoric doesn’t sound foreign at all. After all, federalism and an aversion to aloof centralised power are part and parcel of Swiss identity. The slogan ‘less power to Brussels, more autonomy for the states’ is chanted in different languages throughout Europe. The British have even left the EU under the banner of ‘Take Back Control’ (and considerable paranoia and lies about it).

In the USA, this attitude is reflected in surveys: Trust in institutions goes hand in hand with their distance from citizens. Americans trust their community the most, their state a little less and Washington the least.1

Cititzens trust their local authorities the most and congress the least. 2023. Gallup.

Add majoritarian voting systems

This huge country uses election systems that give the two dominant parties a big advantage: They predominantly use majoritarian elections in which the winner takes it all and the loser goes away empty-handed. There are only a few proportional elections.

Majoritarian elections tend by their logic to reduce the decision to two options. Why? Because few people waste their vote on unpromising candidates if the winner takes it all. People are (entirely reasonably) voting for the lesser of two evils.2

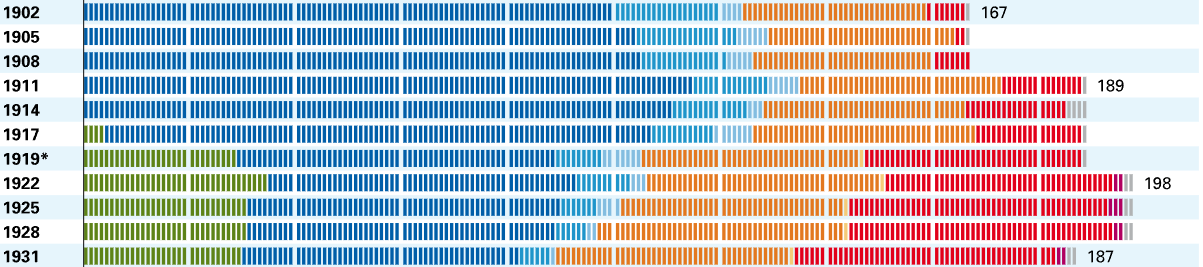

This logic explains why there have almost always been two dominant parties in the US Congress throughout its turbulent history. So it’s the majoritarian electoral systems that cement the duopoly of the Democrats and Republicans since 1857 - not their appeal.

Percentage of seats in the House of Representatives that are not held by the two largest parties.3

In Switzerland, this effect of majoritarian elections was recognised in the first decades of the modern republic and after the First World War proportional representation was introduced. Here is a Swiss election poster from 1918 that I’m sure still speaks from the heart of many an American today. The left image depicts majoritarian representation, the right proportional:

‘Justice raises a nation! Confederates, vote: Yes! on 13 October’ A Swiss election poster for the proportional representation system of 1918.4

‘Justice raises a nation! Confederates, vote: Yes! on 13 October’ A Swiss election poster for the proportional representation system of 1918.4

The effect of proportional representation in Switzerland was abrupt: the ruling Liberals and Conservatives were increasingly joined by the Social Democrats and the BGB. This gave rise to the modern four-party system that guided Switzerland through the turbulent 20th century.

The National Council elections of 1919, the first proportional representation election. Source: Historical Dictionary of Switzerland

The National Council elections of 1919, the first proportional representation election. Source: Historical Dictionary of Switzerland

Our sister republic on the other side of the Atlantic, however, failed to modernise its electoral system. Instead, Democrats and Republicans papered over this flagrant democratic deficit with internal party democratisation: They introduced primaries so that voters could have their say about which candidate their party should nominate to run for president.

This is important for two reasons: First, the parties gave up their role as gate keepers. From before even the civil war, party elites in every state would send delegates to their respective national conventions and pick their national candidate. Several renegade candidates like Donald Trump were actively blocked by the party establishment. However, from the early 1900s until the 1960s, both parties moved to select more and more of their delegates in primaries, which left them little wiggle room for autonomous judgement.

The second reason the move to primaries is important is that the incentives in primary elections are very different from those in general elections: In primaries, candidates must first and foremost convince the party base, not the general population. As Jonathan Rauch wrote in the Atlantic in 20165: ‘Primary races now tend to be dominated by highly motivated extremists and interest groups, with the perverse result of leaving moderates and broader, less well-organized constituencies underrepresented.’ You can see this in presidential elections: In the primaries, candidates play to the poles; then in the election, they play to the centre.

Sort and add loads of money

This shift towards primaries is now being compounded by two developments.

The ‘Great Sort’

In recent decades, constituencies have become much more aligned with one of the parties, resulting in many uncontested one-party districts. To my knowledge, this has occurred at all levels of government and in all elections.

As a simple comparison, I have compiled the results of US presidential elections by district since 1960. The first thing to note is that the political geography of the US has become completely rigid since 2000. While district affiliation was previously dynamic, elections now always follow the same pattern. Districts change or ‘swing’ from one party to another much less frequently.

If you disregard the exceptional landslide victories of Richard Nixon in 1972 and Ronald Reagan in 1984, you will also notice that there are many more dark red or dark blue districts these days. This is because the percentages have become more extreme: districts vote either clearly red or blue. This indicates that they have become more partisan. In other words: In more and more districts, the election is a foregone conclusion.

A clear urban-rural divide has opened up. The Republicans have lost the cities and the popularity of the Democrats tends to decrease with the distance to the nearest city. This is why it is often said that elections are largely decided in the suburbs.

All this also applies to the elections for the House of Representatives: in the majority of seats, one party has a lead of over 10% and there is no real competition.

This ‘sorting’ increases the importance of primaries because the outcome of elections in many districts is clear in advance. Thus the politically relevant audience for the majority of politicians in Washington is not primarily the middle of the population, but those highly motivated activists and hardliners who dominate the primaries. These activist groups can credibly threaten to raise hell with the politicians in the next primary if they don’t honour the deals.

This arrangement makes US politics extremely vulnerable to extreme and populist politicians. The best example, of course, is how Trump hijacked the 2016 Republican Party primaries: ‘According to the Pew Research Center, in the first 12 primaries of 2016, only 17 per cent of eligible voters participated in the Republican primaries and only 12 per cent in the Democratic primaries. In other words, Donald Trump has taken the lead in the primaries by winning a bare majority of just a fraction of the electorate.’6

Causes of the ‘Great Sorting’

A mini-overview of the most important developments that led up to the ‘Great Sort’.

- As a starting point, keep in mind: The US Civil War (1861-1865) was fought because slaveholders in the South wanted to secede from the North in order to preserve slavery. The war ended with the victory of the Union troops under the leadership of Abraham Lincoln - a Republican. The Democrats were still the party of the South at the time and supported slavery.

- In the decades following the war, Republicans largely abandoned their goal of reforming the South. Instead, they became a pro-business economic party.

- With the New Deal coalition of Franklin D. Roosevelt in connection with the Great Depression starting in 1929, the Democrats began to gain popularity in the North and among ethnic minorities. Under John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson, the Democrats then supported some of the demands of the civil rights movement led by Martin Luther King. This did not go down well with their conservative white voters in the South, and resistance formed in the so-called ‘Dixiecrats’. Republicans ‘in the New Deal party systems tended to draw their support from the more affluent, so-called WASPs outside the South and from rural and eventually suburban voters as these communities emerged.’7 Richard Nixon then pulled off the ‘Southern Strategy’ to attract the disaffected white working class in the South, most of whom were evangelicals. ‘With Reagan as the party’s presidential nominee and eventual leader and public face for at least twelve years, the party attempted to keep its establishment wing - which was dominated by the wealthy, the business community, the WASPs (Elements, which might be summarised as country-club Republicans) and rural and suburban voters in the North - with its newfound support among white Southerners, evangelical Protestants and other religious conservatives, and working-class Americans (both inside and outside the unions).”7

- By the late 20th century, this realignment was largely complete. The Democratic Party became identified with liberal to progressive policies centred on social justice, civil rights and an expansion of government intervention in the economy. The Republican Party was associated with conservative values that emphasised limited government intervention, free market economics, and traditional social norms.

The clear sorting is a relatively recent phenomenon that began in the 1990s and appears to be largely a result of shifting party positions in the decades prior. After Democrats launched the New Deal with FDR and supported the civil rights movements, Republicans since Richard Nixon responded with the ‘Southern Strategy’ to appeal to disaffected white voters in the South (who are often evangelicals). The result was that the two parties had a much clearer ideological faultline.

“according to Green, Palmquist and Schickler (2004) few southern Democrats shifted their party identification to the Republican Party. Instead over time, generational replacement occurred where new voters identified with the Republican Party as the older Democratic identifiers passed away.”8

A second factor could be that people with similar political preferences move to similar neighbourhoods - e.g. conservatives moving to the countryside and progressives moving to the city. However, according to Corey & Pearson-Merkowitz, the evidence suggests that such selective migration is of little importance.8

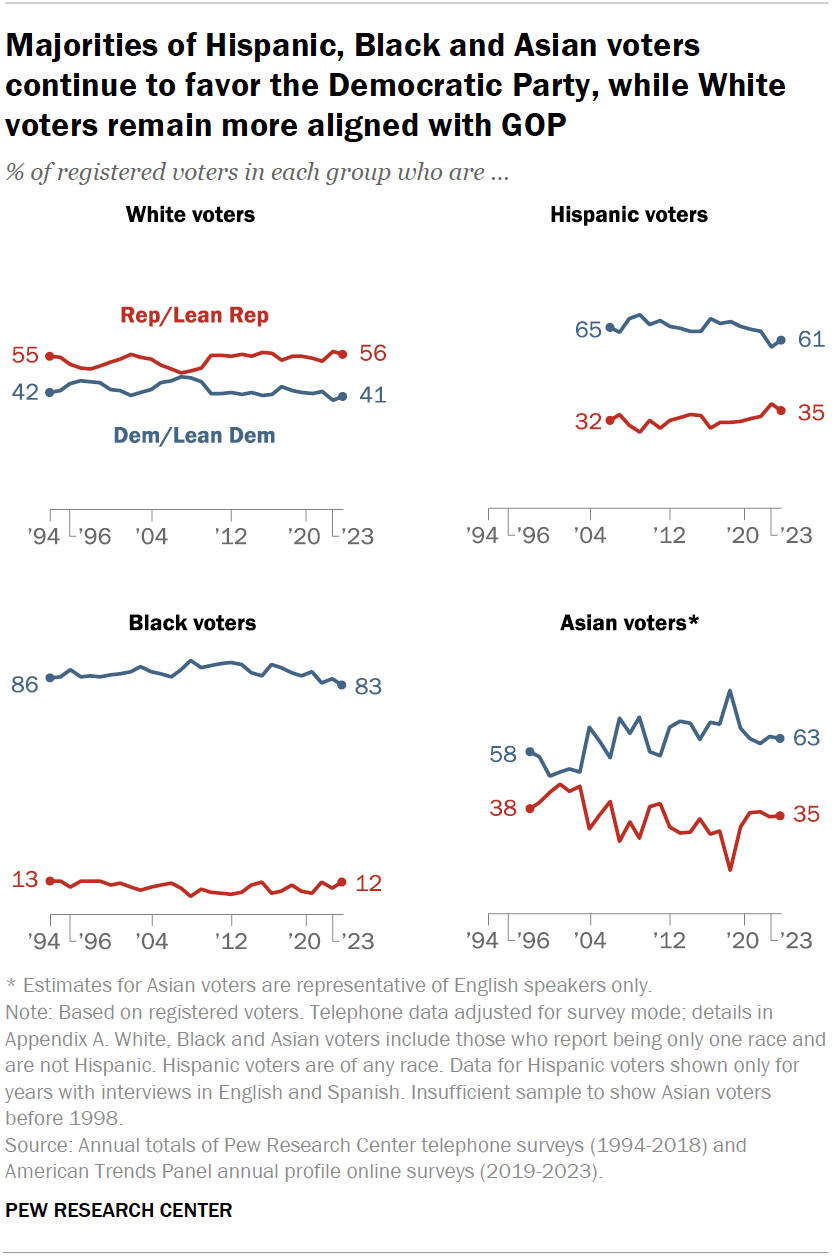

Some authors suggest that a similar sorting process has taken place in relation to ethnic identity. But this already happened in the 1960s.9 Since then, the data does not show much change when breaking down party support by ethnicity.

Source: Pew Research

Source: Pew Research

During the presidencies of Bush Jr. (‘compassionate conservatism’) and Obama, the Republicans recognised this as a problem, as the USA will continue to become increasingly diverse in the future. The party itself wrote in 2013:

“We need to campaign among Hispanic, black, Asian, and gay Americans and demonstrate we care about them, too. We must recruit more candidates who come from minority communities.” Republican National Committee 2013

To a certain extent, Trump’s election campaign could be seen as a rejection of this strategy. He burst onto the political stage with a toxic mix of populism, bullshit, conspiracy theories and xenophobia, which resonated more strongly the more male, poorly educated or white the audience was.

Source: Pew Research

Unbridled ‘independent’ money

Up until the 1960s, the party elites had considerable influence on the electoral process and usually won through with their favoured candidates despite primaries. They then increasingly lost influence through a series of often well-intentioned reforms. For example, the regulation of party financing led to donors channeling their money into election campaigns through private and often anonymous channels.

The ‘Citizen United’ ruling of 2010 has taken this to the extreme: Corporations and lobby groups are officially allowed to spend as much money as they want on election advertising - as long as they do so without coordinating with the candidates. This led to a veritable explosion of opaque ‘outside money’10 in US election campaigns from 2012 onwards, as the statistics from opensecrets.org show.

Stats from opensecrets.org

The shift to primaries has also affected where activists and lobbying groups deploy their resources: increasingly in the primaries, and increasingly concentrated on one of the parties. They watch the behaviour of politicians with the latent threat of supporting a more suitable rival in the next primaries. As David Karol explains:

“To secure the favour and support of these ‘intense demanders,’ candidates [in the primaries] must make political commitments, which increases the gap between the parties. These positions prompt activists and groups to align with one party or the other. The concentration of groups with divergent preferences in competing parties, in turn, increases the pressure for polarisation.” David Karol11

Some examples of such groups:

- Among Republicans, the religious right has become very influential (groups like the Moral Majority, Christian Coalition of America, Focus on the Family).

- The oil and gas industry is increasingly allying itself with the Republicans, environmental groups with the Democrats.

- The gun lobby around the NRA and GOA

What is the target audience?

Overall, the electorate has become more diverse, the party structures weaker and the primaries more important. This combination explains why the US Senate is less polarised. Senate races are fought statewide and less frequently.

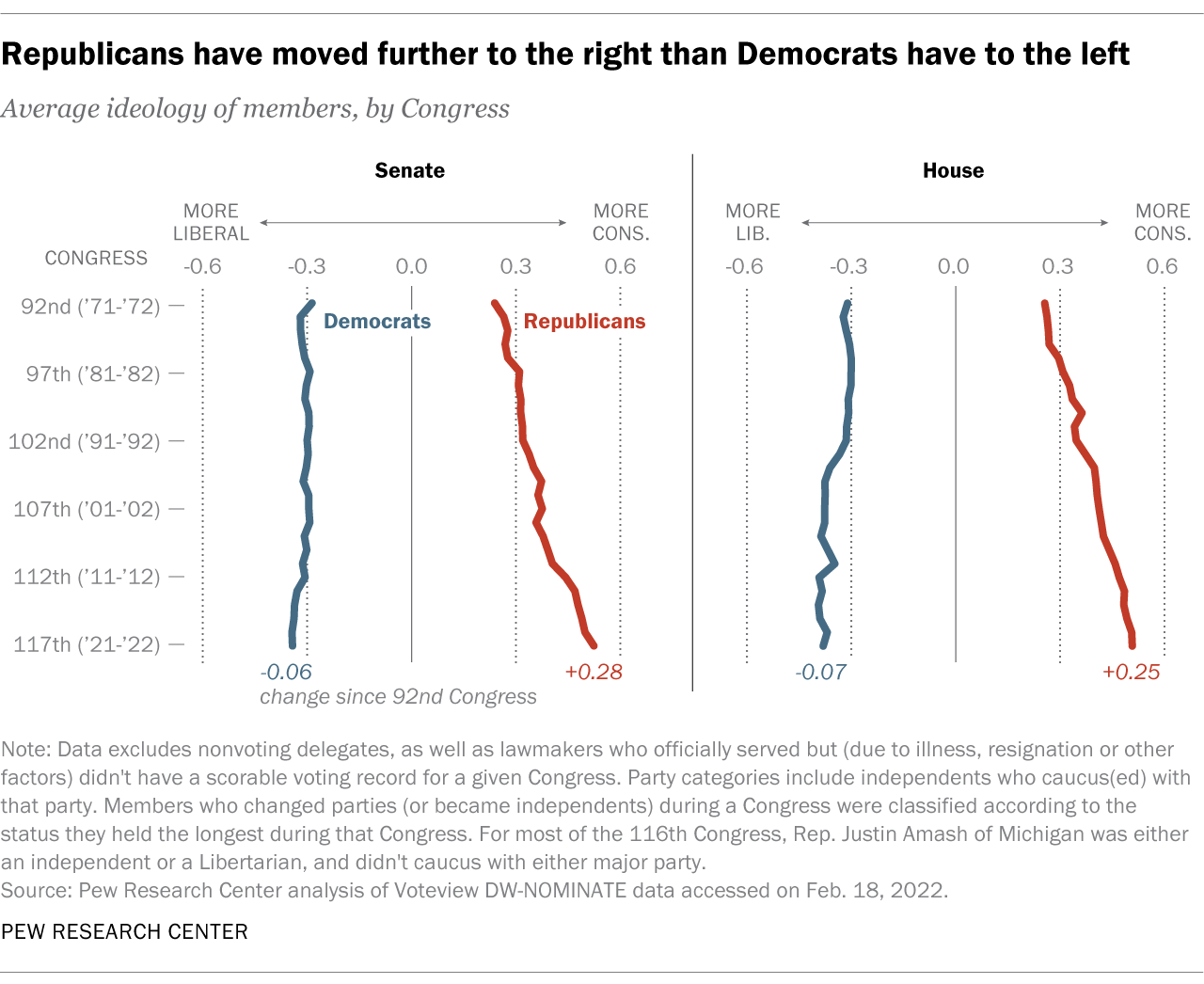

It also explains why Democrats remain the more reasonable party. ‘The evidence clearly shows that the behavioural shifts are largely driven by Republicans,’ wrote Michael Barber and Nolan McCarty in 201312. ‘[A shift] far to the right is more enthusiastically embraced by Republican voters than a shift far to the left by Democratic voters.”13

This is likely due to the fact that the voter base of Democrats is more diverse in the primaries as well. Candidates already have to appeal to different groups of voters. On the Democratic side, therefore, there may be no single force capable of driving the primaries in one direction nationwide.

I haven’t got any further yet. I hope I’ve covered the most important factors. I could expand the analysis to include the fragmentation of the media landscape since Cable News, social media, etc.

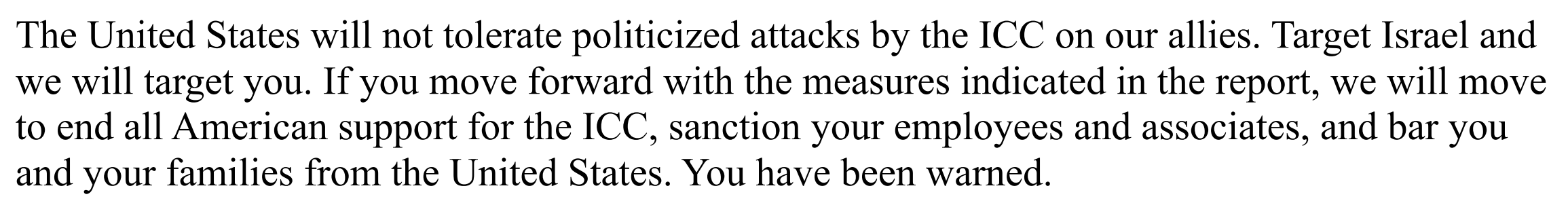

To summarise after this research, I would say: when I see completely irrational Republican politicians threatening International Criminal Court staff and their families in a mafia-style letter again, I wonder what their target audience is.

copy of the letter at Politico.

copy of the letter at Politico.

Because when Ted Cruz, the senator mentioned at the beginning, spoke pointlessly on the Senate floor for 21 hours, it may have seemed ridiculous to us outsiders. But it was so well received by his Republican base that the Americans for Limited Government organisation named him its 2013 Person of the Year.14 So, assuming Cruz represents his base, the sad part is that the ridiculous behaviour begins to make sense.

Footnotes

-

Among federal institutions, those that have less political decision power perform better: The US Supreme Court enjoys the most trust, followed by the President and finally the actual representation of the people: Congress. ↩

-

Heywood, Andrew. Politics. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2007. 209. ↩

-

https://history.house.gov/Institution/Party-Divisions/Party-Divisions/ ↩

-

Ibid. Rauch 2016 ↩

-

Brewer, M. D. & Powell, R. J. ‘The Evolution of the Republican Party Coalition, 1968-2020’ in Polarisation and Political Party Factions in the 2020 Election. Edited by Jennifer C. Lucas, Tauna S. Sisco, and Christopher J. Galdieri. Lexington Books, 2022. ↩ ↩2

-

Lang, Corey, und Shanna Pearson-Merkowitz. ‘Partisan Sorting in the United States, 1972-2012: New Evidence from a Dynamic Analysis’. Political Geography 48 (September 2015): 119-29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2014.09.015. They cite Green, D., B. Palmquist & E. Schickler. (2004). Partisan Hearts and Minds. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ↩ ↩2

-

The term ‘outside money’ refers to political spending made by groups or individuals that are independent of and not coordinated with the candidates and parties. ↩

-

Karol, David. ‘Party Activists, Interest Groups, and Polarization in American Politics’. In Thurber, James A., and Antoine Yoshinaka, eds. American Gridlock: The Sources, Character, and Impact of Political Polarization. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2016. p. 69. ↩

-

https://www.brookings.edu/articles/lessons-from-the-2022-primaries-what-do-they-tell-us-about-americas-political-parties-and-the-midterm-elections/ ↩

-

https://thehill.com/blogs/pundits-blog/lawmaker-news/194072-ted-cruz-2013-person-of-the-year/ ↩